The 1810s marked the true beginning of British colonialism in Oceanyka. Though European contact and small-scale settlements such as Sydney existed prior, it was in this decade that full-scale British settling began in earnest, spurred by the sudden availability of sparsely inhabited land brought about by the Continental Collapse. By the early 19th century, the British Empire sought to secure Oceanyka as both a penal colony and an economic resource. With Britain’s industrial revolution accelerating, the demand for raw materials surged, and Oceanyka presented an opportunity for agricultural and pastoral development. As British settlers, convicts, and administrators arrived in growing numbers, colonial settlements expanded inland, displacing and often violently subjugating Indigenous populations in the process, as evidenced by the Frontier Wars. The British government encouraged land grants to settlers, including ex-convicts, military officers, and entrepreneurs. These settlers, eager to establish self-sustaining economies, turned to livestock husbandry as one of the most viable industries in the vast, largely untamed interior.

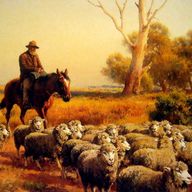

- Sheep pastoralism quickly became the dominant economic activity in the colonies. The temperate grasslands of southern and eastern Oceanyka, similar to those in Britain, provided ideal conditions for grazing. Moreover, the open frontier allowed for expansive sheep runs, where flocks could be reared with relatively low input costs. The industry was further spurred by the introduction of merino sheep, a breed renowned for its fine wool, highly sought after by Britain’s booming textile industry. The increasing demand for fine wool in British markets created an economic boom in the colonies. This early economic success fostered the emergence of a wealthy pastoral class, the Squatter Subculture, whose influence shaped colonial policies and land distribution. These pastoralists lobbied for policies that favoured large-scale sheep stations, often at the expense of surviving indigenous societies, particularly Oceanyka's Nomads.

- As wool exports increased, so did the need for supporting industries. Tanning, wool scouring, and rudimentary textile manufacturing emerged, though the vast majority of raw wool was still exported to Britain for processing. Port towns grew rapidly to accommodate the trade, and infrastructure projects, such as roads and wharves, were initiated to facilitate the transport of wool to markets. This development, however, was largely concentrated around Britain's coastal colonies, while indigenous vassal states were mostly ignored.

- The fine wool boom laid the foundation for Oceanyka’s new agricultural economy but also deepened economic divides. The reliance on large landholdings and sheep stations concentrated wealth in the hands of a few, while convict labour and impoverished Indigenous populations provided a low-cost workforce under harsh conditions, giving way to the rise of the Stockman Subculture. The rapid expansion of sheep grazing also led to significant environmental degradation, including soil erosion and depletion of native grasslands.

Despite these challenges, by the end of the 1810s, Australia had firmly established itself as a key supplier of fine wool to Britain, setting the stage for further agricultural expansion and economic integration into the global market. The wool industry’s early success would continue to shape the economic trajectory of the colonies well into the 19th century, reinforcing Australia's role as a resource-driven economy under British dominion. However, this extractive economy shifted towards mining in the 1850s, particularly during the Australian gold rush, spurring on the Economy of Colonial Oceanyka in the 1850s.