Ostlers have a monopoly on breeding, caring for, and selling horses for profit. This monopoly extends to ponies, mules, and donkeys as well. An all-around master ostler has the skills of livery stable manager, equine veterinarian and farrier, tack and saddle maker, and stud breeder.

Most master ostlers work as stablemasters, providing shelter, food, and water (“livery”) for horses owned by others. The majority of these work with innkeepers, either as free or bonded masters, and care for the horses of the inn’s guests and other travelers. Other masters are bonded to major nobles, legions, and fighting orders to look after the mounts used by knights, other mounted warriors, and members of the household. Ostlers are also found wherever horses are raced.

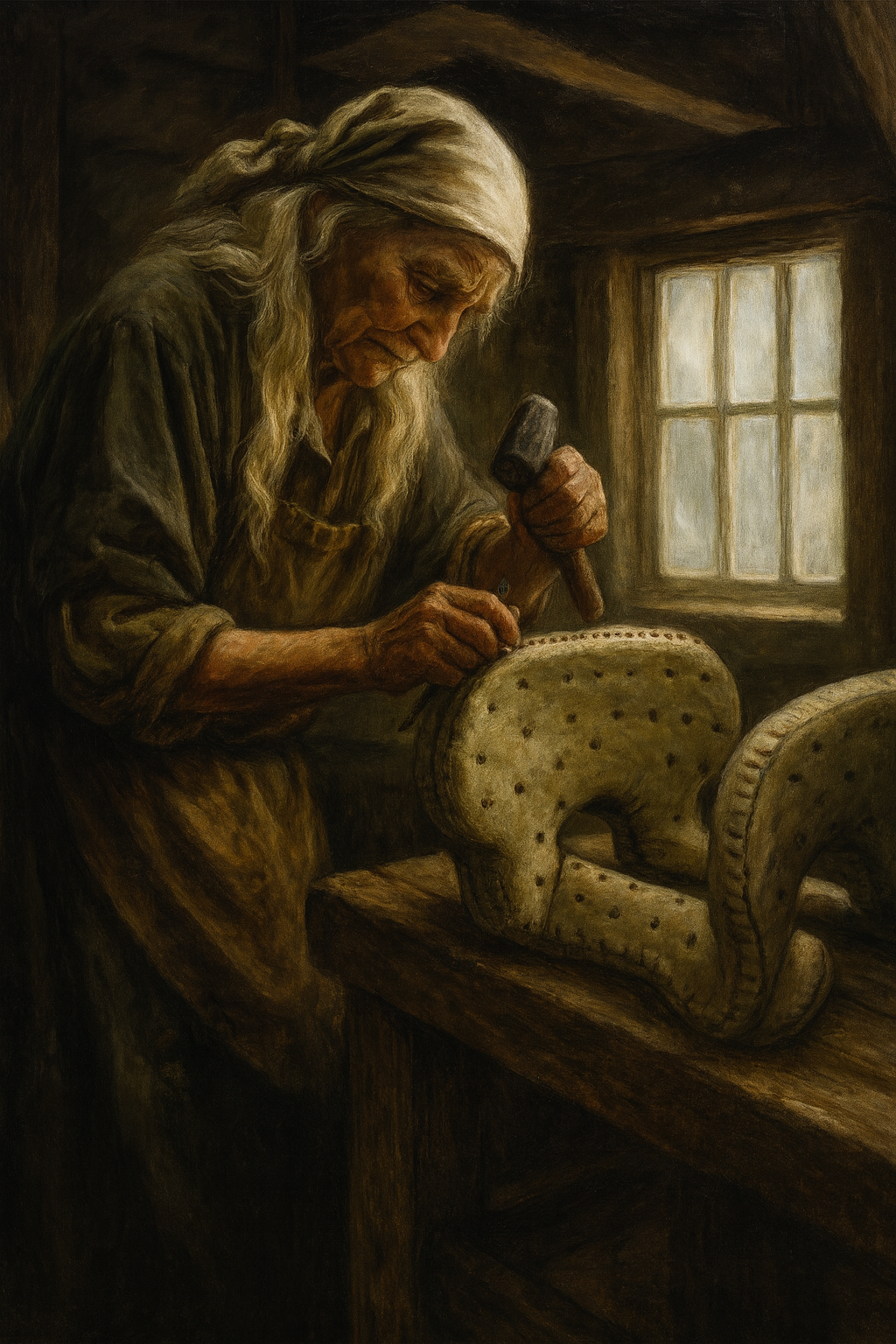

The typical ostler who runs a livery stable will be a jack-of-all-trades, but others in the profession may choose to specialize in one aspect of the trade. Such specialists are most often found in or near larger settlements working as farriers, tackmakers, or studmasters. Farriers look after the veterinary and physical needs of horses, including shoeing them. Tackmakers, often simply known as saddlers, make and repair horse tack, saddles, and related items. Studmasters run stables that specialize in the breeding and training of horses.

A freemaster stablemaster will typically own a stable set in a small paddock or yard. Nearly all large settlements have a common or paddock where ostlers graze the horses in their care. Larger operations may have their own pastures and outbuildings for storing feed and tack. Studmasters usually have large establishments with several stables, outbuildings, paddocks, and often a riding track. Farriers and saddlers typically make do with a simple workshop as part of their dwelling.

Guild Badge

Gold, a bordure vert, a horse-shoe proper. Master ostlers display the guild badge at their stables or workshop to get the attention of potential customers. To differentiate themselves from other ostlers, saddlers often place the badge in the corner of a sign showing a saddle.

Horse Breeds

The breeds most seen on Hârn are listed below and detailed in Horses (COL #4613):

Lankum: Slender, fast, and strong. The most common riding horse on Hârn.

Reksyni: Large and sturdy, but strong. Their loyalty and fearlessness make them excellent cavalry mounts. Their endurance makes them good draft horses.

Khanset: Prized for their speed but rare on Hârn.

Hacherdad: An elegant horse popular with nobles for hunting. Sturdier specimens are also used as pack horses.

Hodiri and Chelni: These small breeds are seldom found outside the ranges of the Hodiri and Chelni tribesmen, but a few ostlers breed them as light draft horses or mine ponies.

Donkey: Small, sturdy, and hardy. Donkeys are used to protect herds of sheep or to breed mules.

Mule: A cross between a horse and a donkey. Mules have a reputation for being stubborn and slow but are intelligent and able to carry heavy loads. See Teamsters (COL #4836)

Saddlers, also known as tackmakers, produce and repair an extensive range of products used on riding, pack, and draft horses. Many of these items are made of leather, and leathercrafting that involves horses is a monopoly of the Ostlers’ Guild, not that of hideworkers. Among the saddler’s goods are saddles, reins, traces, bridles, harnesses, straps, horse collars, pannier bags, barding of leather or cloth, saddle blankets, and pack saddle frames.

Saddlers, also known as tackmakers, produce and repair an extensive range of products used on riding, pack, and draft horses. Many of these items are made of leather, and leathercrafting that involves horses is a monopoly of the Ostlers’ Guild, not that of hideworkers. Among the saddler’s goods are saddles, reins, traces, bridles, harnesses, straps, horse collars, pannier bags, barding of leather or cloth, saddle blankets, and pack saddle frames.