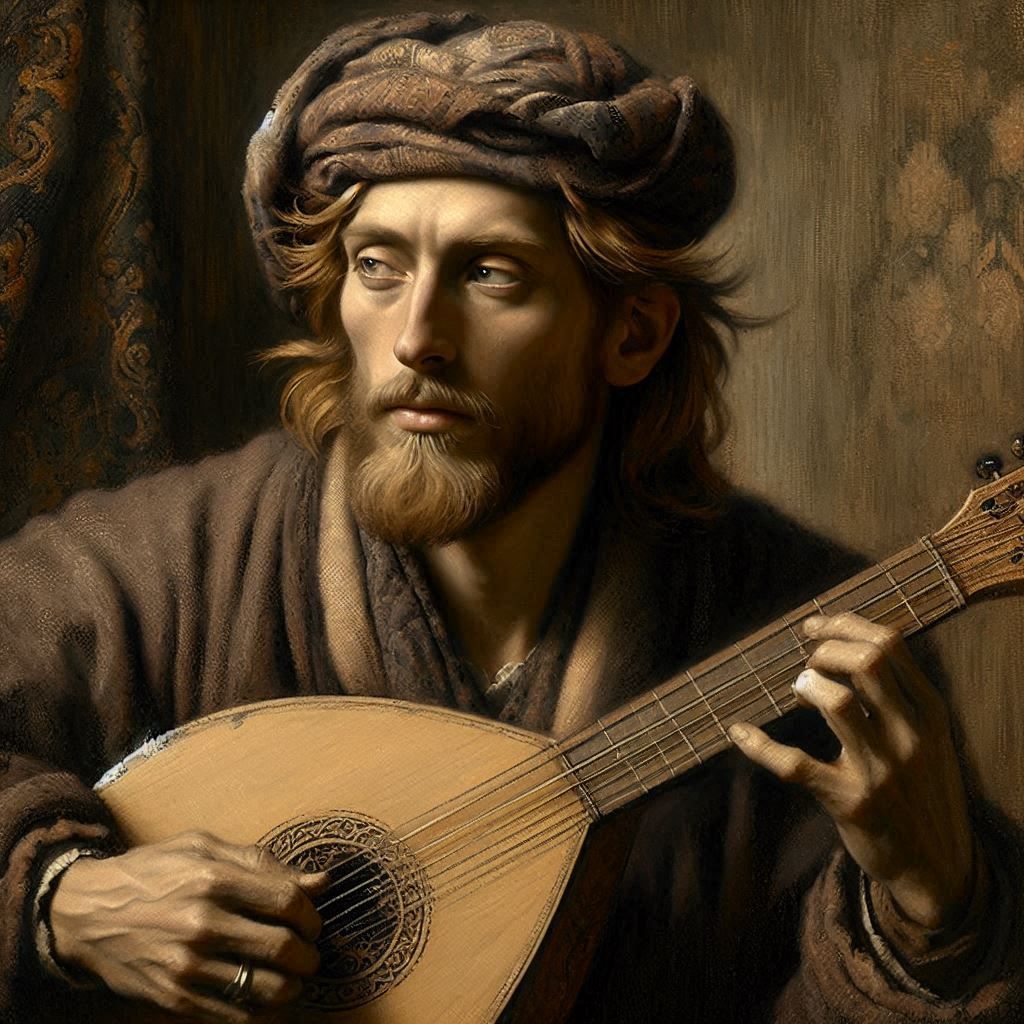

Harpers are professional musicians. Most earn their living as performers, although some specialize in the crafting of fine musical instruments such as the harp, flute, drum, horn, and lute. Truly great harpers can make instruments of seemingly awesome enchantment and play them with such skill as to coax any emotions they wish from their listeners.

The College of Harpers is a member organization of the Mangai, the association of Lythian guilds. The College has a monopoly on the production and sale of musical instruments but not on singing or making music in general, even when done for profit. Nonetheless, membership has its benefits, as many civic leaders will hire only guilded harpers to entertain at fairs and other events they sponsor.

Harpers are an essential part of the musical traditions of virtually all Lythian cultures. Master harpers are part of royal households and many landholding noblemen employ the services of a personal bard to entertain them and their families. Other harpers find regular employment at houses of courtesans or accompanying thespian troupes.

Many harpers support themselves by traveling about and performing in inns or taverns or wherever they can find an appreciative, and paying, audience. The College has guildhalls in towns and cities across the Hârnic realms to provide itinerant members with accommodation and rehearsal space. The public can visit these guildhalls to hire musical entertainment and purchase musical instruments.

Itinerant harpers play an important role in the conveyance of news, tales, legends, and oral histories. Minstrels from afar are always in great demand by audiences eager for songs and tales of strange folk and exotic places. The veracity of the tale is less important than the entertainment the harper provides in recounting it. Ivinian skalds, noted for their epic tales of heroes and villains, are welcome novelties in the southern realms. Sindarin harpers seldom play for outsiders but are without doubt the best at these arts, beloved for their beautiful but often unfathomable songs.

Harpers can use their talents to praise good leaders or damn those who have done poorly. Busking musicians offer social commentary to delight or incite the crowds. The opinion of the authorities is expressed in how quickly the town guard is sent in.

Guild Badge

Journeyman harpers are given an engraved and enameled pin bearing the emblem of the College of Harpers. A master harper’s badge has a gold border to denote his or her rank. Guildsmen who desire anonymity can adopt a stage name and the appellation “of the Black Harp” but will often display the badge to acknowledge their status.

Journeyman harpers are given an engraved and enameled pin bearing the emblem of the College of Harpers. A master harper’s badge has a gold border to denote his or her rank. Guildsmen who desire anonymity can adopt a stage name and the appellation “of the Black Harp” but will often display the badge to acknowledge their status.

Income

An average bonded master harper can expect to earn 42d per month, plus room and board. A journeyman receives 30–60% of a master’s wages, depending on experience, plus room and board.

Townsfolk can visit a local guildhall to hire harpers to entertain at their feasts and civic events. The negotiated fee (typically 3–12sp per performer) may be supplemented if the performance was especially well received.

Harpers also offer lessons to the public in singing and playing instruments. Typical clients include children of wealthy families, courtiers, thespians, and courtesans.

Harpers are accomplished minstrels, musicians, bards or skalds. Most earn their living as performers although some specialize in the crafting of fine musical instruments such as the harp, flute, drum, horn, and lute. Truly great harpers can make instruments of seemingly awesome enchantment; a few players have been able to coax any emotions they wished from their listeners.

Harpers are accomplished minstrels, musicians, bards or skalds. Most earn their living as performers although some specialize in the crafting of fine musical instruments such as the harp, flute, drum, horn, and lute. Truly great harpers can make instruments of seemingly awesome enchantment; a few players have been able to coax any emotions they wished from their listeners.

The College of Harpers has little presence in

The College of Harpers has little presence in  A skald’s education is deemed incomplete until he or she has read the Idjarheim stones. These standing stones were carved by Idjar, one of Sarajin’s sons. They bear an incomplete but unique record of Ivinian folk history, although the oldest stones are severely weathered. Some of the eddas were brought to Idjar by wandering skalds; having one’s name inscribed below such a work is a great honor.

A skald’s education is deemed incomplete until he or she has read the Idjarheim stones. These standing stones were carved by Idjar, one of Sarajin’s sons. They bear an incomplete but unique record of Ivinian folk history, although the oldest stones are severely weathered. Some of the eddas were brought to Idjar by wandering skalds; having one’s name inscribed below such a work is a great honor.