Potters are found in nearly every major settlement, yet their guild is one of the least influential within the mangai. Only the largest towns have more than one franchise in operation; most potteries are small operations dedicated to local markets. Bonded master potters are employed in larger potteries; only rarely are they employed in noble households as is common with other master guildsmen.

Potteries typically employ only a handful of workers—an urban franchise with more than six guild members is unusually large. Recent advances in kiln building and operation, however, are changing this pattern and larger operations that employ a dozen guild members or more can be found in some places.

In one of the Mangai’s many paradoxes, the glassworkers’ guild is both the closest ally and leading competitor of the potters’ guild. At one time, the two guilds were one and still the issues that affect one are important to the other, leading to frequent alliance between the two guilds. Advances in knowledge are rarely shared between the two guilds, however, as they compete with one other to supply wealthier households with the necessities of everyday life.

Village peasants often ignore the legal monopoly the potters’ guild claims. Every village, it seems, has at least one “village potter” who makes crude, utilitarian ware for himself and his neighbors. Such wares are substandard in almost every respect—he uses raw surface clay, with none of the additives that produce proper clay bodies, he fires at low temperatures in clamps (covered pits) rather than proper kilns, and his work is generally crude in appearance.

The guild generally tolerates the village potter because most villagers cannot afford the guilded potter’s wares, and because the amateur does not offer serious competition. Anyone who can afford them will almost always favor the quality wares of the guilded potter over the crude fare made in a village hovel. For peasants, such quality ware is a sign of wealth and status. For the others, the craftsmen and the nobility, there is no question of their patronage. When the village potter is found infringing on the guild’s business, however, the guild and mangai take swift action.

Guild Structure

The potters’ guild structure is the same hierarchical system common to most of Lythia’s guilds: apprentice, journeyman, and master. Master potters elect the local guild chapter’s board of syndics. The syndics choose one of their number as guildmaster. The guildmaster represents the local chapter to the grand chapter of the guild and to the mangai.

Potters typically enter apprenticeship at age 13, become journeymen at age 19, and become masters at age 22. Though there is nothing precluding marriage while still a journeyman, most guildsmen delay marriage and family life until after they achieve rating as a master potter. As a result, most master potters are about 37 years of age when their eldest child enters apprenticeship and, if still alive, are about 46 years old when that child achieves a master’s rating and returns home to inherit the family franchise.

Since the training time for a master potter is nine years, and most spend at least 20 years working as a master potter, there are about as many master potters as there are apprentices and journeymen combined.

Apprentices

The guild admits two apprentices for each retiring master in the expectation that one will fail to complete his training and become a master. Before applying to the local guild chapter’s board of syndics for membership, each aspirant must first secure written acceptance from a freemaster potter willing to take him as an apprentice. The board almost always grants apprenticeships to the heirs of master potters, with the “extra apprenticeship” normally granted to the other offspring of freemaster potters. Other individuals with natural talents or heavy purses are sometimes admitted to the guild if they are able to find a sponsoring freemaster.

Apprenticeship normally lasts six years. To ensure proper discipline, apprentices are rarely allowed to serve in a parent’s franchise, though many return home to take employment as journeymen or bonded masters.

Apprentices do not earn wages but are supported with room and board at an approximate cost of 24d per month. Generous masters may also grant them a small amount of spending money.

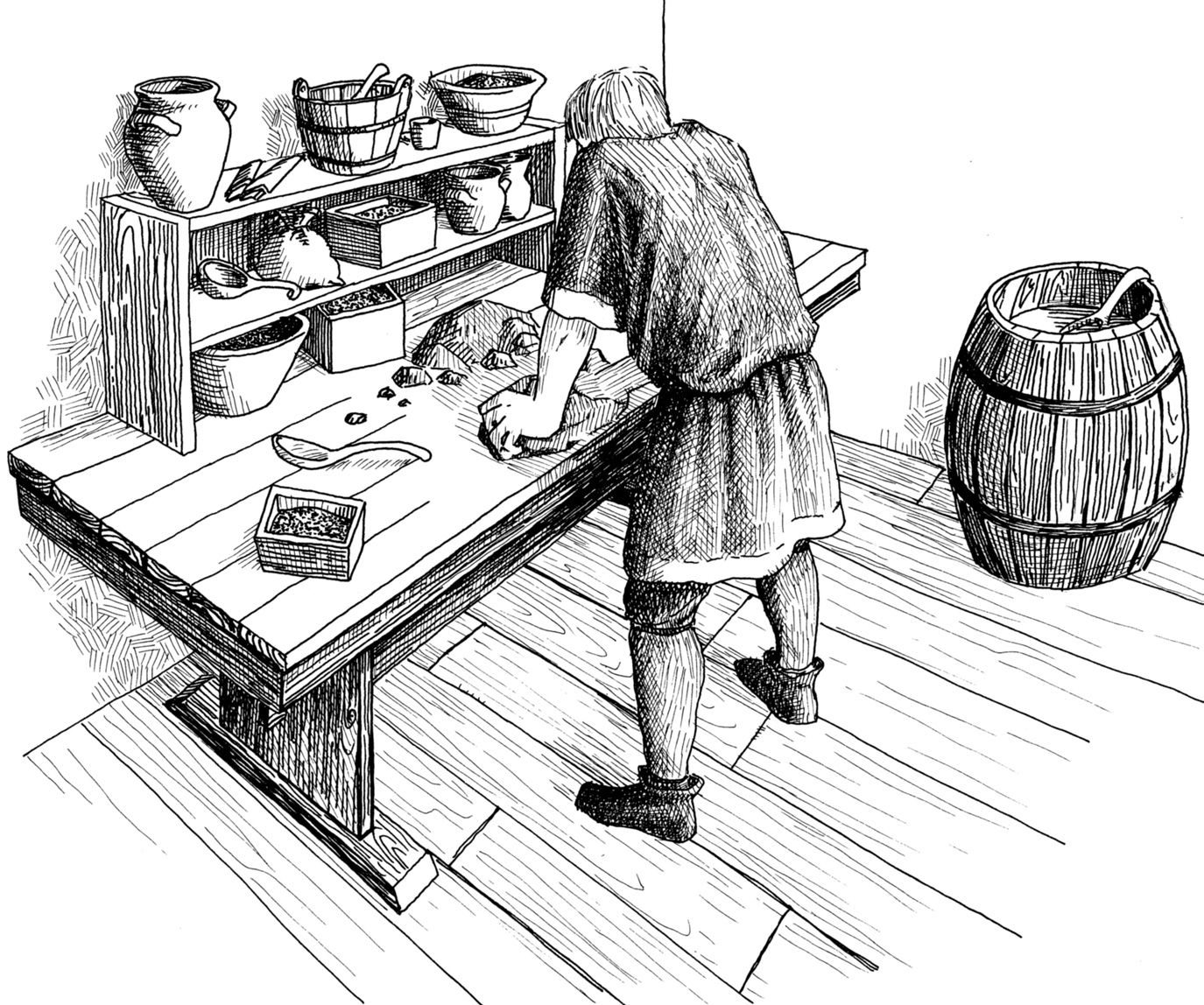

Apprentices spend long hours digging clay from pits knee-deep in water and using wooden shovels to turn clay in seasoning pits. Marching in place, they tread on clay in old-fashioned pug tanks. They laboriously grind and sift minerals and refined metals into fine powders, and mix and wedge clay and clay bodies to prepare them for use by journeymen. They cut cords and cords of firewood into lengths suitable for use in the pottery’s kilns, and sort the stacked fuel by type of wood. They load and unload hot kilns, and spend long hours tending small but hot fires inside tiny fire pits. And, in the process, they begin to unravel the secrets of alchemy.

They learn to identify the properties of various clays and other minerals by their appearance. They learn to predict the color of the final product based on the contents of the clay body and the compounds in the slips and glazes used for decoration and waterproofing. They learn to control the temperature of the kiln through careful selection and mixing of the type of fuel added to the fire pit. They learn how to modify and control the atmosphere inside the kiln, creating ones that are oxygen-starved or sodium-enriched, to cause controlled and predictable results. They note how the careful addition of certain minerals to the clay in just the right quantities changes the temperature at which it vitrifies, and how that affects the porosity, durability, and heat resistance of the finished product. And they learn to create the compounds of minerals and metals used in making waterproof glazes of dazzling colors.

Once apprentices have demonstrated proficiency with the science of pottery, they begin to learn its art. In this, the master can but provide the opportunity for the apprentice to find his own style and technique.

Journeymen

The geographic dispersal of the potter’s guild lends an air of great import to the testing of candidates for journeyman status. Eligible apprentices accompany their masters to a regular convention of the board of syndics to demonstrate proficiency in both the theoretical and practical knowledge of the potter’s craft.

Typically, proficiency is established during a series of oral examinations. However, some examination boards require applicants to identify various minerals and other components of clay bodies and glazes based on appearance and properties when exposed to heat, both alone and as part of various compounds. The apprentice’s master normally vouches for the candidate’s artistic abilities when he nominates the apprentice for examination.

Candidates who successfully complete testing are immediately granted the certificates that confer on them the rank of journeyman. By tradition, new journeymen do not return with their former masters but use the convention as an opportunity to find employment with a new master within the guild chapter.

In addition to room and board, journeymen are paid wages depending on skill and experience. Generally, a first year journeyman potter is paid 20d per month, a second year journeyman receives 30d per month, and a third year journeyman earns 36d per month. The cost of room and board for each journeyman is about 24d per month.

Journeymen are expected to travel from one settlement to another, serving different masters of their guild as they perfect their craft. After three years experience as a journeyman, potters may apply to the board of syndics for rating as a master potter. Journeymen who desire rapid advancement typically spend only one year with each master, leaving for employment elsewhere once they obtain a favorable recommendation. A master must employ a journeyman for at least a year before he can grant his recommendation. Three favorable recommendations, each from a different master, are required before a journeyman may apply for status as a master potter.

Masters

Candidates for certification as a master potter must present themselves for examination during a regular convention of the guild’s board of syndics. With the written recommendation of three masters as evidence of having mastered the art and science of their craft, candidates are normally required only to demonstrate the ability to manage the day-to-day business operations of a franchise. Examinations are generally oral, though in some cities written examinations are becoming more common.

Unlike journeymen, master potters are not expected to travel. Most settle down and begin families. Masters who will inherit the family’s franchise generally return home to take employment as a bonded master. Those without such prospects seek employment as a bonded master in a large pottery where they typically earn 60d per month—more if room and board is not provided. Bonded masters who are married expect additional pay in lieu of room and board. Especially skilled or experienced masters may receive additional pay and incentives.

The guild manages its membership so that there are about three times as many masters as there are franchises. This ensures that there are enough skilled masters to meet the demand for quality pottery and that even the smallest shop has the opportunity to take an apprentice.

Board of Syndics and Guildmaster

All masters, free or bonded, are voting members of the local guild chapter. They elect from their membership a governing board of syndics that in turn appoints one of the board members as the chapter’s guildmaster. The size of the board is governed by the size of the local chapter. A five-master membership is most common, but every board consists of an odd

number of members whatever its size.

The guildmaster heads the local board and represents it to the local chapter of the mangai. He also sits on the grand chapter’s board of syndics that elects the guildmaster of the guild’s grand chapter.

The board of syndics is empowered to award and revoke existing franchises, create new franchises, set “fair price” guidelines for utilitarian wares of specific qualities, and rule on disputes between chapter members. The board normally convenes once every six months at a time and place announced at least two months in advance.

During these regular conventions, the board handles routine matters of administration and hears complaints from chapter members, but its main business is to consider applications for apprenticeship and examine applicants for advancement to journeyman and master. Hearings concerning award, revocation, or creation of franchises, however, always take precedence.

Chapter Organization

The geographic boundaries of the guild’s local chapter usually coincide with the boundaries of the local chapter of the mangai. Typically, a major market town, such as a free city or castle town, forms the nucleus of the chapter with guild members at other nearby settlements included in the membership.

Grand chapters are composed of a number of local chapters. Typically, the boundaries of grand chapters coincide with political boundaries so that all local chapters within a state are members of the same grand chapter. In the more-populated areas of the Venarian Sea, however, it is not uncommon for the boundaries of a republic or empire to include

two or more grand chapters of the guild.

Another notable exception to the typical pattern is the still very sparsely populated island of Hârn. There, where some estimates put the number of guild franchises to be as few 180 potteries, local chapters of the potters’ guild include entire kingdoms and together form a single grand chapter.

Pottery Franchises

The primary purpose of the potters’ guild is to provide economic security to its members by safeguarding the guild’s monopoly on the making and sale of ceramic wares, and by controlling the number of franchises available within the chapter. A franchise is a license from the guild entitling the holder to own and operate a pottery within the jurisdiction of the local chapter. The franchise does not include the property, buildings or other equipment the master must obtain or provide in order to actually conduct business. Franchises are granted only to master potters; master potters who own franchises are known as freemaster potters.

Franchises are heritable, and most franchises are passed down from parent to child. Franchise holders may also sell their franchise to another qualified master for whatever price they are able to negotiate. Prices are based on the profitability of the franchise, but most are bought for a price between 1,440d and 7,200d. Having negotiated the purchase of the franchise, the buyer must also negotiate the purchase of real estate, buildings and other equipment, or make arrangements to provide his own. The buyer also bears the expense of the origination fee that transfers the franchise into his own name (240d, paid to the guild chapter to cover the costs of licensing the franchise through the mangai with the local government or lord).

Masters who die without heirs, go bankrupt, or have their franchises revoked for cause forfeit their franchise to the guild chapter. Such franchises are offered for sale by the board of syndics. When possible, the guild uses its own funds to purchase the real estate and capital equipment of failed franchises to make them available to prospective buyers.

The guild may also make loans available to prospective buyers, especially if the franchise was financially solvent before it was reacquired by the guild. In the case of a failed franchise, prospective buyers must prove they have the capital to sustain the operating costs of their first year. In the case of more than one prospective buyer, the board may accept bids to determine which candidate will be granted the franchise, though a simple vote by the board may suffice.

A master potter may petition the board of syndics seeking the creation of a new franchise. Approval of such a petition is very unlikely in areas of minimal population growth, but in areas of population or market growth the petition may be granted.

Before the board considers an application for a new franchise, petitioners are required to demonstrate that the new franchise will not adversely affect the economic security of existing franchises. Successful applicants typically demonstrate that the ratio of existing franchises to population density or market sizes do not meet current guild guidelines and that a new franchise is needed to keep prices stable.

Once the economic security of existing franchises is assured, applicants describe their plans for acquiring the real estate, buildings, machinery and other equipment required to establish the franchise, and demonstrate that they have the capital required to execute their plans. Most boards also require proof of sufficient capital to pay the wages and support costs of all employees through the first year of operation. Loans from the guild to cover these capital costs are sometimes made available.

If a majority of the board’s syndics vote for approval of the application, the board acts through the local chapter of the mangai to obtain a business license from the local government or lord. Bribes to facilitate a favorable outcome are considered a routine expense of the process.

Once approved, the board collects a small franchise origination fee from the applicant and issues the appropriate license. Origination fees for a new pottery franchise are 240d.